$ 60.00

About

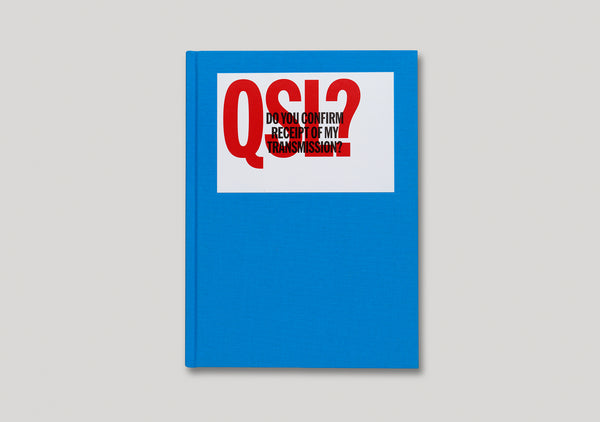

A collection of over 150 “QSL cards”, QSL? chronicles a moment in time before the Internet age, when global communication was thriving via amateur, or “ham”, radio operators.

Discovered by designer Roger Bova, the distinctly designed cards follow the international correspondence of one ham, station W2RP, who turned out to be the longest-standing licensed operator in The United States.